The Smallest Number That Can't Be Described in 20 Words

Recommended prerequisites:

- Turing Machines

- The Halting Problem

A Paradox

Consider the set \(S\) of all positive integers that can be completely described in 20 words or fewer. This set contains a lot of numbers. For example, “two to the power of ten” describes \(1024\) in six words. “One hundred and seven” describes \(107\) in four words. “The first ten decimal digits of pi” describes \(3,141,592,653\) in seven words. And “the smallest prime number greater than a billion” describes \(10^9+7\) in eight words. Let’s say that we only allow English words in our descriptions – not digits – so that we can’t have phrases like “5386” describing \(5386\) in one word (that would make the entire premise trivial).

We know the set \(S\) is very large – it easily contains all integers up to at least a trillion (anything smaller can be spelled out: “seven hundred twenty-two billion four hundred nineteen million …”). However, |\(S\)| must be finite. After all, there are only a finite number of English words, so there can only be a finite number of phrases built from at most twenty English words. Now we ask the question: what is the smallest element that is excluded from \(S\)?

What is the smallest positive integer that cannot be completely described in twenty words?

Let \(x\) be this number. Here we run into the paradox. The phrase “the smallest positive integer that cannot be completely described in twenty words” completely describes \(x\)! This contradicts our definition that \(x\) be indescribable in twenty words.1

Something must have gone wrong in our chain of reasoning. In any logical paradox, there is always a step in which a faulty assumption is made. This faulty assumption almost always deals with some form of self-reference: an idea that is defined in terms of itself. Take perhaps the most famous paradox of all, the Epimenides paradox. This sentence is false. The self-reference here is explicit – the truth value of the sentence is defined in terms of the truth value of the sentence (specifically, it’s the negation).

In our case, the self-reference is harder to detect because it is implicitly contained in what we mean with the word “describe”. Specifically, when we say a number is “describable in twenty words”, we mean that there exist some twenty English words that specify what that number is. But “describe” itself is an English word. So our ability to describe a number includes the power to reference its ability to be described. This is where self-reference is built into our premise. The very use of the word “describe” breeds paradox, just as the assumption that we can assign truth values to arbitrary sentences breeds paradox in the Epimenides statement.

A Patch

Despite the paradox, it still feels like our original question is still attempting to ask something meaningful. Shouldn’t there exist numbers that cannot be expressed in twenty words? And shouldn’t there be some smallest such number? Perhaps there is a way to restore the spirit of the original problem while avoiding all self-reference. We can do this by refining and formalizing the word “describe.”

Instead of talking about numbers being described in some amount of words, we will talk about numbers being computed by an algorithm of some length. This is essentially what we’re doing when we use any non-self-referential sense of the word “describe.” The description “two to the power of ten” is simply an algorithm telling us to start with \(2\) and multiply it by itself \(10\) times. The description “the first ten decimal digits of pi” can be thought of as an algorithm that computes and then outputs the first ten digits of \(\pi\), perhaps using more and more terms of a Taylor series.

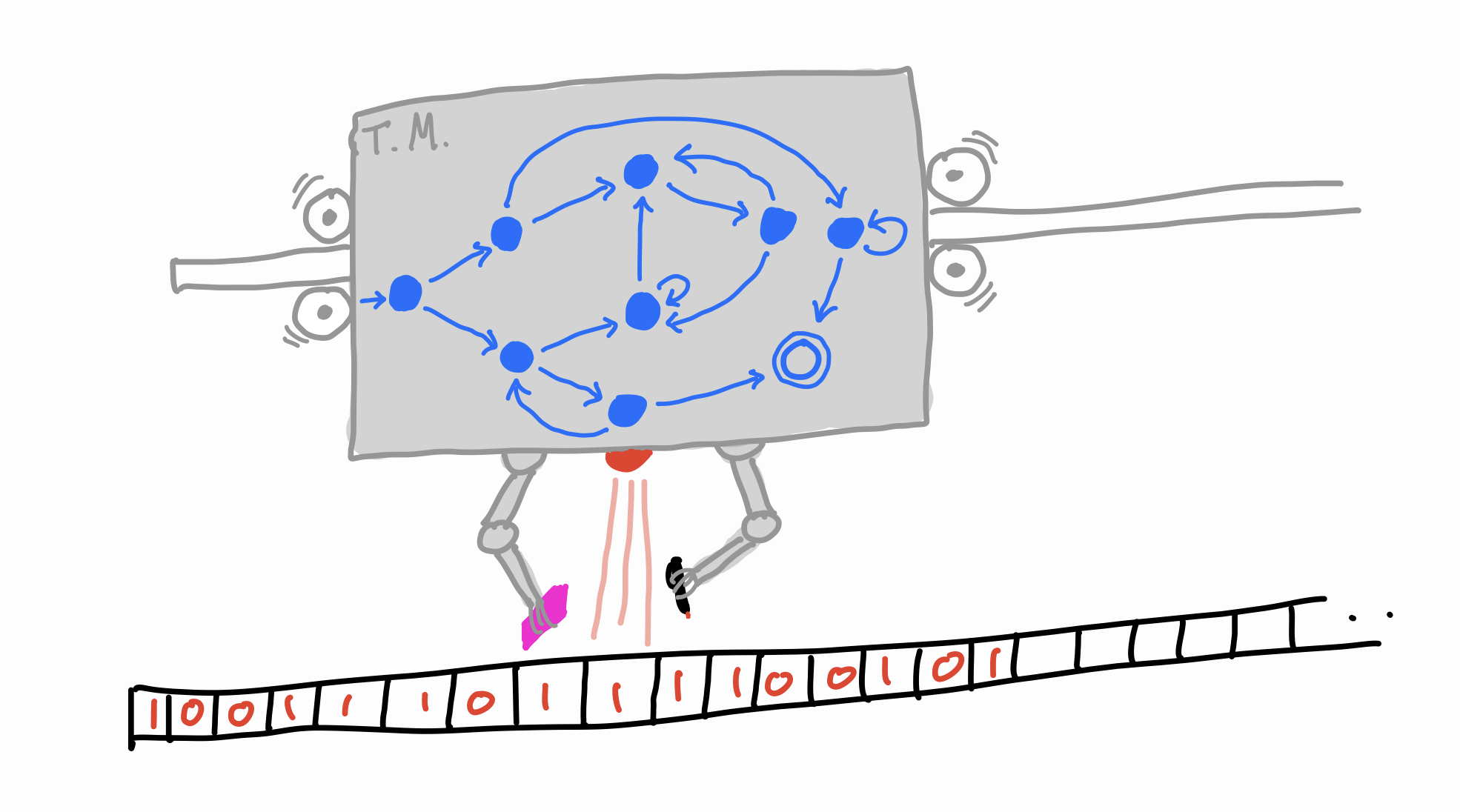

To be truly formal, we can talk about algorithms in terms of Turing Machines. The Turing Machine is a conceptual model of an algorithm in which the only operations allowed are reading and writing bits from an infinite tape2 and moving back and forth along the tape (there is also a special “halt” operation which terminates the algorithm). The sequence of operations it performs is dictated by a deterministic finite automaton – essentially, a finite collection of internal states together with a function that tells the machine how to transition between these states (and which operations to perform during each transition). The integer that a Turing Machine computes is simply the sequence of bits left on the tape (read in binary) after it halts, if it ever does.

The exact details of how Turing Machines work are not important here. We only care about two key facts. First, every Turing Machine is finite. Although the operations it carries out on the tape (and its final output) can be unbounded, its “brain” itself must be described by a finite number of states. Secondly, any algorithm can be performed by a Turing Machine.3 This means that we are not limiting the definition of the word “compute” at all by restricting ourselves to thinking about Turing Machines. If it can be computed, it can be computed by a Turing Machine.

Now we can modify the original question with our new terminology:

What is the smallest positive integer that is not computed by any Turing Machine with at most 20 states?

There is a finite number of Turing Machines that have at most 20 internal states, in the same way that there are finitely many computer programs that use at most 20 lines of code.4 But now we have eliminated all self-reference. A Turing Machine describes an algorithm on the lowest possible level: read/write/move-left/move-right tape instructions. This prevents the word “computable” from making any reference to the notion of computability, in contrast with the way the word “describable” references the notion of being describable. English words are inherently self-referential. Turing Machines are not. Our paradox is resolved.

Thus, we can expect that our question has an actual answer. There must be some smallest positive integer uncomputable by a Turing Machine with 20 states. I am less interested in what this number is (it’s probably pretty large) than I am in what it represents: the smallest number that has a certain amount of “complexity” to it.5 This, I think, is what the spirit of the original question is getting at. Patch successful.

A Proof of Halting Uncomputability

Although our initial goal was to remove self-reference, we can actually do the opposite – simulate self-reference – to come up with a proof that the Halting Problem is uncomputable. The Halting Problem asks: given an arbitrary Turing Machine (or an arbitrary algorithm), will it eventually halt? Or will it get stuck in an unending sequence of calculations? Formally, \(HALT: \{\text{Turing Machines}\} \to \{0, 1\}\) is a function that maps every Turing Machine to a Boolean – whether or not it halts.

It is well-known that \(HALT\) is uncomputable. In other words, there is no Turing Machine that takes as input an encoding of a Turing Machine and always outputs whether or not it will halt. The standard proof of this fact is very clever. On a high level, it harnesses the contradiction of the Epimenides paradox (“This sentence is false.”) to show that no such Turing Machine can exist. Here, I will present an alternate proof that makes use of our “smallest number undescribable in twenty words” paradox instead. We do this by simulating self-reference in Turing Machines.

Proof. Assume for the sake of contradiction that there exists a Turing Machine \(H\) that computes \(HALT\). Say that \(H\) uses \(n\) states. Now, consider the pseudocode for the following algorithm \(G\):

define algorithm G:

S = {} // a set of integers

for each Turing Machine M with at most n+1000000 states:

if H(M):

run M(), add the result to S

// find smallest number not in S

i = 1

while S contains i:

i = i+1

return i

The pseudocode for \(G\) can be translated into a Turing Machine. This Turing Machine will have \(n\) states that represent the “code” for \(H\) (think of this as a subroutine built into \(G\)), along with extra states that handle the rest of the computation: initializing an empty set \(S\), iterating through all possible Turing Machines of a certain length, simulating these Turing Machines, and then finding the smallest number not in \(S\). This extra work is definitely not trivial – simulating the Turing Machines alone requires the functionality of a Universal Turing Machine. However, it should only take some constant number of extra states above the \(n\) required for \(H\) – here, I’ve assumed it takes at most \(10^6\) extra states. The specific constant is irrelevant for the proof; if it turns out we actually need more, just increase the constant.

This is where our original paradox comes in. We have designed \(G\) so that it computes the smallest positive integer that is not computed by any Turing Machine with at most \(n + 10^6\) states. But \(G\) itself is a Turing machine with at most \(n + 10^6\) states! Furthermore, \(G\) is a well-defined algorithm that is guaranteed to halt, so it must compute some number. This is a contradiction. We are forced to conclude that our assumption – that there exists a Turing Machine \(H\) computing \(HALT\) – is false. \(HALT\) is uncomputable. \(\blacksquare\)

If you’re comfortable with the standard proof of the uncomputability of \(HALT\), this line of reasoning should feel familiar. The key idea in both proofs is that the ability to compute \(HALT\) gives us too much power. Specifically, it gives us the power to indirectly perform self-reference by iterating through and simulating all possible computer programs, one of which must be the program itself!

Non-uniform Computation

\(HALT\) is uncomputable. But any prefix of \(HALT\) is computable. Define the partial function \(HALT_k\) to tell whether or not an arbitrary Turing Machine with at most \(k\) states halts. In other words, \(HALT_k\) agrees with \(HALT\) on all inputs of size up to \(k\) and says nothing about larger inputs. Notice that for any given \(k\), \(HALT_k\) is computable. After all, there are only a finite number of Turing Machines that have at most \(k\) states, so \(HALT_k\) could be implemented with a giant hard-coded lookup table.6

A cool feature of our proof is that, with a slight modification, we can achieve a bound on the computability of \(HALT_k\). Specifically, for any \(k\), \(HALT_k\) cannot be computed by a Turing Machine with less than \(k - 10^6\) states. The reasoning is as follows. If \(HALT_k\) were somehow computed by a Turing Machine \(H_k\) with \(k-10^6\) states, then the algorithm \(H\) in the previous proof could be replaced with \(H_k\). The remainder of the proof still works because all Turing Machines passed into \(H_k\) have at most \(n + 10^6 = k\) states. We achieve the desired contradiction with \(G\) as before.

Notice that our bound on \(HALT_k\) is logically stronger than the uncomputability of \(HALT\). The former implies the latter because it asserts that a Turing Machine computing \(HALT_k\) for larger and larger \(k\) (in the limit, this is \(HALT\)) must have more and more states, which is impossible because a Turing Machine must be finite.

A Historical Connection

We start with an abbreviated story of mathematical logic in the early 20th century.

In Grundgesetze der Arithmetik (The Foundations of Arithmetic 1903), Gottlob Frege attempted to establish the philosophical foundations of mathematics. To Frege’s dismay, Bertrand Russell was later able to use Frege’s axiom of unrestricted comprehension to create a paradox (does the set of all sets that do not contain themself contain itself?). This proved Frege’s axioms inconsistent. Fast forward to the Hilbert Program of the 1930s, in which David Hilbert and his followers once again sought to develop the foundations of math. Cognizant of Russell’s paradox, they made sure that no direct self-reference was possible. But then Kurt Gödel showed that in any mathematical system that has sufficient power, there will be true statements that can never be proven. This dealt a lethal blow to the Hilbert Program. The key to his proof rested on an indirect self-reference paradox in which he encoded the notion of provability of a statement into the statement itself. This is known as Gödel’s incompleteness result.

Compare that story with a high-level overview of what we accomplished in this post. First, we created a contradiction by abusing the recursive power of the English language. We patched this self-reference by limiting our discussion to formal algorithms and computation. Finally, we realized that even with this restriction, we can achieve indirect self-reference by simulating programs inside programs. This led us to a deep result of uncomputability: the Halting Problem.

The analogy here is striking. The expressivity of language stands for Frege’s offending axiom. Computation stands for proof. Uncomputability stands for incompleteness. Somehow, the same fundamental ideas of expression and self-reference pop up over and over in the foundations of math, logic, and computer science.7 This universality, in my opinion, is what makes our story beautiful.

Ending note: A few months after writing this post, it came to my attention that this paradox and the accompanying uncomputability results have already been extensively studied by many smart people. See the Berry paradox.

-

Some readers may recognize this idea from the classic joke proof that every number is interesting. The proof goes: assume there are some uninteresting numbers. Consider the smallest such number. But then this number must be interesting, by nature of it being the smallest uninteresting number! We conclude that there can be no uninteresting numbers. ↩

-

In this post, unless otherwise specified the Turing Machine receives no input. The tape starts out blank. This is what I mean when I say “a Turing Machine computes a number,” as opposed to the more common “a Turing Machine computes a (partial) function.” The \(HALT\) function we discuss later is more accurately described as \(HALT\_ON\_BLANK\). ↩

-

This is known as the Church-Turing Thesis. ↩

-

In a programming language that has a bound on the length of a line of code (my apologies, Python and your arbitrarily nested lambda functions). ↩

-

This goes by the name Kolmogorov complexity. ↩

-

This is just a way of stating the fact that \(UNARY\_HALT \in P/poly\). Any function, including \(HALT\), is non-uniformly computable – for every \(n\) there exists an algorithm that computes \(HALT\) for inputs of size \(n\), but there is no way to systematically come up with this algorithm given an arbitrary \(n\). ↩

-

This is the main theme of Hofstadter’s book Gödel, Escher, Bach. ↩